| HOME | BOOKS | COMICS | RECORDS | NEWS | PEOPLE | PICTURES | ORDERS | HISTORY | office@savoy.abel.co.uk |

| Savoy: The Most Banned Publishing Company in Britain b y D a v i d M a t h e w Interview with Michael Butterworth and John Coulthart for the Ministry of Whimsy (2000) |

|

|  SAVOY'S FLYER ADVERTISEMENTS are a work of genius. SAVOY'S FLYER ADVERTISEMENTS are a work of genius. Firstly, they look professional, with sharp, clear, eye-catching print, and a précis of the company's selling points, its manifesto in gobbet form. "Books, Records, Comics," it reads, and the website location (www.savoy.abel.co.uk) follows. Although a company having its own website is commonplace these days, even the idlest later glance at the site in question hints at arduous attention to detail—to professionalism and pride. Savoy is a set-up with technological savvy, we think, as we read on. A list of oddly connected organisations and personalities is mentioned. Not all of the names, needless to say, will be familiar; but the list is, if not a unique selling point, then a pretty damned unusual one. An assumption of eclecticism, of a reader's willingness to focus on disparity and anomaly—not to mention that the house will represent a kiss and tell session between high and low art—is quickly made. In one way or another, Savoy is the house which links the rock band New Order to the philosopher Schopenhauer; or glues Martin Amis to the "differently-funnied" comedian Bernard Manning ("differently-funnied" if we are being tweely politically correct, or incorrigibly racist if we are not). And on who else's publicity bumph would you see, as if clashing swords, the mighty Madonna and the scurrilous London tabloid, The Mirror? And then there's the bullseye—the punchline. Appealing as it does to the furtive snoop in every one of us, it is a fantastic selling point and in total it reads as follows: Savoy: "The most banned publishing company in Britain". It's official.

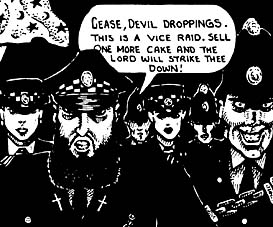

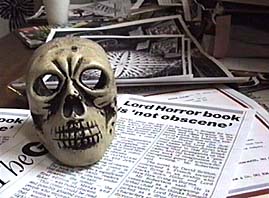

Frequently fighting unfavourable odds, Savoy has been producing provocative material for over a quarter of a century. Furthermore, the new work produced shouts loudly and forcefully that there is no letting up on the workload. Towards the end of the '90s a lull occurred, true; but over the years—what with police raids and even prison sentences having haunted the house—Savoy has learned to lick its wounds and fight back. Why? And how? Obviously part of Savoy's longevity is due to the modesty of the operations, of which more below. But also there is the feisty dedication of purpose, and the stubborn refusal to kow-tow, to take into consideration. One of the advantages of this particular press, despite the diversity of subjects (some would say "victims") discussed, there has always been a guiding light, a singularity of intention. Indeed, in accordance with several other small presses, Savoy gives the reader the impression of being admitted into an exclusive club—or indeed being adopted by a new, strange family. It's not so much a deliberate attempt at clannishness from the publishers as it is—what?—a dedication to a readership unable to find the sort of material he wants to read. Whether you happen to enjoy each of Savoy's endeavours (and by the simple law of averages, this seems unlikely), the quality of thought and the labour of love that went in are swiftly evident. None of which—and not a web of earlier friendly phone conversations in order to make arrangements—stills the interviewer's heart as he travels north to meet Michael Butterworth and John Coulthart, who are two of the three key players in the Savoy business. (The third, David Britton, was not absent through illness or a prior engagement: he actually refused to meet me, as indeed he refuses to meet all interviewers. He wants no more publicity than he has already had. See below.) Most interviews are preceded by a period of worry. In the case of Savoy, I suppose I was expecting a guarded self-protective edge to their answers: and I was wrong. But I figured that any group that had already been prone to ''more" than the customary perils of publishing (a few stroppy letters, quite possibly a bit of plagiarism) would be on the offence, rather than the defence. But I was wrong. Primarily, what the good people of Savoy wished was to present their side of the story. "We like to talk about the work," John Coulthart said midway through our conversation, "because Savoy had acquired a reputation as a publishing house that goes to court a lot. And obviously there's a lot more happening than that." Before any clarification could begin, however, a rare and well-thought-out challenge to the interviewer was underway—it had to be tackled. I had to ''find" them. Oh, I had an address of course, and detailed instructions: the problem was that a locksmith's business was where a publishing house should be. After drilling up and down the street, I entered this shop and was invited to clodhop my way up a set of asthmatic wooden stairs. They breathed heavily with my every tread. As it turned out later, the keymaking business is not a front, but is one of the pies in which the publishers have their fingers. Michael Butterworth is the co-founder and editor of Savoy, and John Coulthart is an artist and Internet technician. Butterworth makes a karate-chop gesture and indicates a chair that I fear will fail to take my weight. (I fear it might fail to take the weight of a cigarette, but I manage to remain seated throughout.) We begin. Butterworth met David Britton, he says, "...through the small press publications each of us used to produce separately before we started Savoy—Weird Fantasy, Wordworks, Bognor Regis, Concentrate, Crucified Toad, Corridor (see Pre-Savoy). I had a reputation as being one of the inner circle of the young New Worlds writers in the '60s English New Wave of science fiction. Dave had one bookshop going by that time, called House on the Borderland." David Britton's shop, opened in 1972, was the first specialist science fiction shop outside London. "What we wanted to do," Butterworth explains, "was publish maverick writers and artists we thought were being neglected, or who—like Harlan Ellison, say—were regarded as being difficult to market... Savoy was built on enthusiasm and tenacity and sheer bloody-mindedness. We were the only publishing house of any worth outside London for many years." They gave Henry Treece's Celtic tetralogy its first paperback edition almost twenty-five years after the original Bodley Head books appeared; they undertook a lavish re-launch of urban novelist Jack Trevor Story's career and published a slew of other disparate luminaries—American fantasist Harlan Ellison, Lancashire children's artist Ken Reid, M John Harrison and others. They became—and still are—one of the main British publishers of Michael Moorcock. Their output was unified by the audacious marketing strategy of mass-marketing larger format paperbacks with jackets which combined the high art seriousness of Picador with the pulp garishness of Ace or Lancer Books. Butterworth says: "They were lush, slick and illustrated inside. But we came up against rack sizes in bookshops. Frankly, our books wouldn't fit in! We were trying to force change. With hindsight, in trying to cater for a readership we felt part of but which wasn't being catered for, we were a little bit ahead of our time." Since then, inevitably, both highs and lows have been experienced. "The high point as publishers was when we were distributing through New English Library. Our titles went all around the English-speaking world. But we never got money back quick enough to keep going as a viable company. Effectively what we had was a spider's web of bookshops, which—as soon as I met Dave—we expanded all over Manchester, and beyond: in Manchester, Leeds and Liverpool. One of our managers opened a shop in Nottingham. These funded our publishing ambitions... But the high point creatively, is what we're doing now, with Dave's Lord Horror creation. But we haven't really followed the usual business patterns or channels." Indeed, the latest Britton novel, Baptised in the Blood of Millions, already looks ready for as rough a ride as the previous two novels, Lord Horror and Motherfuckers; for, despite trying hard, Savoy are unable to find a printer willing to print it. Down and down the spiral. Things got worse. One of their shops was "put totally out of business by the Manchester IRA bomb in 1996" and another shop—their principle cash generator—was closed down in 1998 by redevelopment. But about those raids: "They started long ago in 1976, when James Anderton became the Chief Constable of Greater Manchester," says Michael Butterworth. "Our shops were at their height, and earning us an incredible amount of money which we poured into the publishing. Dave had modelled them on a London bookshop called Dark They Were And Golden Eyed, which was the first shop in the country to cater for youth culture. It dealt in a mixture of science fiction, fantasy, horror, film, back-issues, imports, underground culture and so on. And to this mix we added erotica of various kinds, underground records and bootlegs—and played very loud music!" John Coulthart adds: "The shops in Manchester were perceived as a focal point for nefarious activity. Anyone who was anyone called in to the shops: Tony Wilson was there, the Buzzcocks, The Fall; the drummer from Joy Division worked in one of Dave's shops as a teenager. Ian Dury... They used to get people to sign the wall, and then, sadly, the building was demolished... Anderton didn't like anything we had anything to do with." Butterworth: "We've lost count of the number of raids we've had, but up until that time we must have been raided about 40 times, under Section Three of The Obscene Publications Act. This was from around '75 up and into the early '80s, which was when we started fighting back. We've had at least 60 raids in total. The police raids have now finally stopped—after 25 or so years." In 1980, police conducted simultaneous raids on all of Savoy's outlets—including its publishing offices. The company was prosecuted for publishing two erotic science fiction novels: and it was officialdom's first attack on the company as ''publishers', as opposed to booksellers. The Gas by Charles Platt and The Tides of Lust by Samuel Delany were part of a line of over-the-top erotic fantasy which no other publisher would touch. Virgin Books had attempted a similar line, but the corporate powers that be had put a stop to it before any of the titles appeared. When the police raids began in earnest, "Dave got 28 days in jail," says Butterworth. The experience catalysed Britton, and started his writing career. He began work on an idea for a novel which had been germinating for years, but which lacked a focus. Lord Horror, the novel, a fantasy treatment of the Holocaust, co-written by Butterworth, was published by Savoy in 1989 to immediate acclaim and outrage, almost ten years after the raid that led to Britton's imprisonment. The police mounted a second comprehensive raid. By now, Savoy had begun a campaign that openly attacked James Anderton in print—and the novel itself contained a caricature of the police chief. Needless to say, the raids and court appearances escalated. Savoy had ceased to be a paperback publisher—that phase ended in bankruptcy in 1981, a penury caused partly by the raids and by NEL's own problems—but they kept going as book packagers (which is when they did The Bernard Manning Blue Joke Book, packaged to their old distributor, NEL—and a collection of Gerald Scarfe artwork, which eventually came out from Thames and Hudson). Next up was a new publishing phase, based mainly around the Lord Horror character. This basically consisted of originating work in-house. Since then comics and records as well as books have emerged. Butterworth: "The magistrate who confirmed the charges on the novel said that it was racist, obscene and likely to corrupt. The appeal judge who lifted the charge on the novel, said the comics were more lurid, and therefore more likely to corrupt the less literate—a condescending note similar to the one struck by the prosecutor in the Lady Chatterley case, when he asked the jury, 'Would you allow your wives or servants to read this book?'" David Britton was jailed again in 1993, for the sale of material seized in the large 1991 raid. After protracted battles, in a separate hearing in 1995, the comics from this raid were found obscene—despite the testimonials of noted defence witnesses. Savoy was not allowed a jury trial. Because of the outdated view of comics held by the courts, Butterworth and Britton decided to fight the appeal on those grounds that they should have been allowed to put the case before a jury, rather than the issue of obscenity. They went to the High Courts in London. In 1996 they tested a 1964 undertaking by law officers to Parliament that serious publishers caught up in trawls for pornography under the Section Three law would receive a jury trial if they were to ask for one. Savoy had asked for a trial, and been refused. They lost the test case. The positive addendum to this quagmire of litigation was that "By fighting back, taking it through to the High Court, the police have actually stopped bothering us. They've realised, I think, that we're too much ''trouble'.!" So the process has lost momentum? Coulthart adds: "Well, Anderton started off at a ludicrous pitch, where he was raiding newsagents for copies of Mayfair." (Note: Mayfair is the name of an erotic magazine.) "That sort of loopy energy was powering it to begin with. And the vice squad was pretty corrupt at that time also..." Coulthart: "If you agree with the obscenity law, you have to agree with the wording of it. And the wording of it is: the thing that's being looked at should have no merit whatsoever. Various categories: literary, artistic, scientific, serving public interest, and so on. So for this magistrate to say these comics were obscene meant that one of my comics—which I spent a year drawing—had no artistic value. A lot of critics have told me it's the best thing I've done. I was trying to explain to the magistrate various artistic influences, but it was all swept aside, as though all that effort counted for nothing. Which in their eyes was the case." Butterworth: "According to the prosecution, who could not otherwise explain the patently 'serious' nature of our work, we deliberately put artistic references in to the strips, to camouflage their obscenity." Coulthart adds: "The situation is weighted on their side—seriously weighted. When you're sitting in court you have to restrain yourself from saying, 'Now hang on a minute...' But at the end of the day, they haven't stopped us doing what we want to do, so what the hell? We're going to go on doing it...When you've come this far—when you've had your stuff banned—you've nothing to lose. It's sharpened our mind. The first Lord Horror comic series, now banned by the courts, is about fascism during the Second World War—so you have notorious book-burners inside the very books that are being destroyed by other people. The irony is astounding." New projects for Savoy are rife, and ripe for the picking, as Butterworth explains: "The Web is ideal for promoting small publishers; it immediately increases the exposure of an eclectic business like ours," and he then goes on to discuss Savoy's other new endeavours: "A CD reading of Lord Horror, and a CD of (Eliot's) The Waste Land, both read by PJ Proby." (Proby was more or less rescued from alcoholic oblivion by Britton, who at the very least restored some of the ex-singer's identity and professional pride.) "We're also trying to extend the multimedia concept we've been pursuing, to moving image." A projected Lord Horror film, directed and written by David Glass, was unfortunately (but routinely, given the film business anyway) "delayed in all the upheaval and removals of the last eighteen months", but the news is still positive that this project is still likely to go ahead. Says Butterworth: "We shall be back on the case with this one as soon as..." Additionally, the seventh Reverbstorm comic book has just been published (only one to go to complete the series) and they have two new big projects on their hands. "The first is a new deluxe hardback line of fantasy works. The Exploits of Engelbrecht by Maurice Richardson, has already appeared. Forthcoming titles include our takes on Colin Wilson's The Killer and David Lindsay's A Voyage to Arcturus, also: Anthony Skene's Monsieur Zenith the Albino (a main influence on the formation of Michael Moorcock's Elric character), and a John Coulthart-illustrated edition of Hodgson's House on the Borderland." The second 'big project' is the entirely unexpected and unplanned one of finding a printer for Baptised in the Blood of Millions. The search for a printer has now become a hunt. "The novel's finished, and was scheduled for Spring 2000 publication. In many ways the climate is worse now than it's ever been. The full money is on the table, yet no one wants it. I don't think we were really expecting that." More power to the mighty Savoy elbow! • Savoy note: Baptised in the Blood of Millions finally saw print in February 2001. David Mathew was born to the north of England and returned to a nearby spot after living in Wales, Cairo and Gdansk. He is a regular reviewer for Interzone magazine and a prolific writer of articles and interviews. On the other hand, his fiction appears with the swiftness of a mollusc, but to date he has a perfect hit-rate—although he expects that to change now that he has completed his first novel, Torso Redux. He is a copy-editor, proof-reader, teacher of refugees, and a writer of educational materials. He lives in a nice part of the world. |

| Main People Page |

This is as good a place as any to discuss a few of the low points.

This is as good a place as any to discuss a few of the low points.