| HOME | BOOKS | COMICS | RECORDS | NEWS | PEOPLE | PICTURES | ORDERS | HISTORY | office@savoy.abel.co.uk |

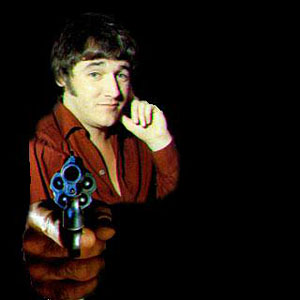

| PJ Proby: Could the now-penniless singer be ready for a comeback? b y R o b e r t C h a l m e r s The Independent, September 30th 2007 |

Robert Chalmers meets the man who outraged Middle England in the 1960s with his trouser-splitting pop performances. Robert Chalmers meets the man who outraged Middle England in the 1960s with his trouser-splitting pop performances. FORTY YEARS AGO, PJ Proby travelled to Soweto, where he consulted a Sangoma, or Zulu clairvoyant. The Texan singer—already world famous for the aberrant talent that prompted writer Nik Cohn to describe him as a genius and "with James Brown, the most electrifying performer I ever saw"—watched as the fortune-teller cast bones from a leather cup. The Sangoma related extraordinary facts about his visitor's past. When he addressed the rock star's future, the fortune teller fell silent and then began to weep. You can only guess at the developments the clairvoyant anticipated that day. It could have been the multiple bankruptcies, or the years this former friend of Elvis Presley would spend working in Huddersfield as a shepherd. Perhaps it was his trial on a charge of shooting his wife, the day he blew up his house in Beverly Hills, or that unfortunate afternoon in 1978 when he attacked his secretary with an axe. Possibly it was a vision of the star's performance at Fagin's club in Manchester, in the late 1980s: Proby left the stage after half an hour, telling the audience: "I'm sorry. I cannot go on. I am suffering from gonorrhoea, more popularly known as the clap." Or maybe the Sangoma's vision of PJ Proby's future was right here, where my research for this article began, at the Flymail bait and tackle shop, in Aberystwyth, where owner John Morris is examining a box of live ragworm. He warns me against putting my hand into the writhing mass of millipede-like creatures. "If they get hold of your finger," he says, "you have to stand on them." Morris, an engaging Welshman of 60 or so, edges past a display of protective hats with names like "Mosqui-Go!" and takes down a cherished album of photographs of the singer, whom he manages. "I saw them all," Morris says. "Lennon, Hendrix, Jagger. But Proby was—is—the greatest." This isn't my first attempt to interview the singer, who last spoke to the national press in 1996. Previous requests foundered when he asked for money. This time, Proby, 68, makes no such demand. A week or so after first talking with Morris, I'm on the doorstep of the American's current home, a cottage on land adjoining a busy roundabout outside Evesham, in what Proby pronounces as "Woostershire." We sit in the garden, in the late morning sunshine. This isn't really Proby's kind of weather: a life-long insomniac, he says he only truly relaxes in a storm. Thunder is what he loves. Thunder makes him sleep. His land looks like a piece of Mexico, dotted with apple trees and totem poles. We take turns at throwing a ball for Tilly, his dachshund. Proby looks fit and alert, though he occasionally forgets places and names. "What year was it," he asks himself at one point, "that I died?" He pauses. "1992. At Fort Lauderdale in Florida. I went there with my [then] girlfriend, Elizabeth. I'd just left the penitentiary." "Why were you in there?" "I'd argued with Elizabeth and," Proby adds, with a roguishly plausible look, "she beat herself up." "How did you come to die?" "Elizabeth got me out of prison. I woke up the next morning and there was vomit all over me. She said: 'You've been foaming at the mouth and throwing up.' I told her: 'I need a beer.' There was none. I needed some of those little blue pills—Ativan [lorazepam, a tranquilliser]. At the pharmacy they told me I needed admitting to hospital. I said: 'I'd need a beer first.' Then, Elizabeth told me, I took one step and dropped deader than a doornail. The paramedics were trying to get my heart started. It stopped twice there and once in the ambulance. When I woke up, I had tubes coming out of my body." "Did you see the path of golden light, or the gates of hell?" "I saw nothing," Proby says. "That was the last day I took a drink." If he'd died when he might have done—in the mid-1960s, when he was ordering Jack Daniels for breakfast and hosting nightly parties where he'd discharge his .45 more often than some would deem prudent—PJ Proby would need no introduction. Early death, as his former associates Ritchie Valens, Eddie Cochran and Elvis Presley might testify, is the one foolproof way to cement a reputation in popular music. But Proby survived, and there is probably no star whose profile has plummeted so rapidly and from such a height. He had top 10 hits in the mid-1960s with songs like Hold Me and Somewhere, but his greatest talent was for performance. He developed increasingly exaggerated stage mannerisms, one hand cupped behind his ear, the other reaching out as though attempting to adjust an invisible side-mirror. He was the first white singer to introduce an unambiguously direct sexual element to his act. If Presley's choreography could be likened to the trouble-free eroticism of a chorus girl, PJ Proby's instincts were closer to those of a low-life stripper. "Am I clean?" Proby would scream. " Am I clean? Am I pure?", massaging his thighs as he executed pelvic thrusts whose coarse vigour appalled the parents of his young female audience, especially on his first tour of Britain. "I am an artist," Proby announced at the time, "and I should be exempt from shit." This proclamation went sadly unheeded in the UK where he was banned from every major theatre, and by BBC and ITV; a fever of prohibition that began after his velvet trousers split on stage at Croydon in January 1965. To his irritation, censorship is what he tends to be remembered for. "My trousers split across the knees," he says. "Never to the crotch. These days Iggy Pop gets his tackle out on television and nobody pays any attention." Proby's controversial reputation, and his highly mannered articulation (in his ballad I Can't Make It Alone, "away" becomes a seven-syllable word) have obscured the tremendous quality of his voice, which remains unaffected by decades of punishment. "On stage," Nik Cohn wrote, in his 1969 classic Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, dedicated to Proby, "he was magnificent; the most mesmeric act we had ever seen. He was intuitive, hysterical, imaginative, original and irresistible ... as a ballad singer, he outclassed Sinatra, or any of them." After hit singles, appearances with The Beatles, and an acclaimed performance as Cassio in Catch My Soul, Jack Good's 1969 rock adaptation of Othello, the singer's career should have looked after itself. But with Proby, whose memories include being strapped into the electric chair aged five, by his grandfather, a prison governor ("a shame," one ex-wife said, "that they didn't turn it on"), things were never straightforward. At the height of his popularity, he owned a Chelsea house decorated with the helm of a sailing-clipper, urns ("big ones") and wildebeest heads. He lived with an entourage headed by his best friend Don Grollman, "The Bongo Wolf", the disabled son of a Hollywood dentist, who wore vampire fangs moulded from porcelain. "Bongo had a Quasimodo limp," Proby recalls. "He looked like something out of The Munsters." "Where is he now?" "Last I heard, Bongo had been kidnapped in Louisiana by this drug pusher." He throws Tilly's ball into his orchard. He was first declared bankrupt in 1968. Now he's supported by "some DSS thing called Pension Credit" . Proby is looked after by a group of loyal friends, led by Morris in Aberystwyth, and Pat Hayley—his manager for many years, who went on to produce Michael Barrymore. "How did a woman like Pat tolerate you for so long?" "She was in love with me." His last steady partner, singer Billie Davis, moved out of this house years ago, making a succession of withering observations in the popular press. (" In the time that we dated," Davis complained, "he had one erection. It lasted three hours. He was so pleased that he spent the whole night smiling at it. I didn't get a look in.") "It's just me here now," he says. "Just me and Tilly." He was born James Marcus Smith, in Huntsville, near Houston, Texas, in 1938. Though his upbringing was middle-class—his father was an affluent banker—his childhood memories are traumatic. Proby's recollections are, to put it mildly, inconsistent. He tells me, for instance, that he became sterile at seven—"so all these girls that say they were pregnant by me, never were". He's previously talked about his illegitimate daughter in America. In 1965 he told The Sunday Times that he has "several kids" . On the history of his boyhood, he remains curiously dependable. His mother Margaret suffered numerous defeats in the battle against infidelity. Her most significant affair was with Arthur Moers, the family doctor—an alcoholic whose preferred method of extinguishing the gas stove was to urinate on it. On the day Margaret told James Smith Senior she was leaving, Proby, 10 at the time, watched as his father loaded three bullets into his 300 Savage rifle, at which point he was overpowered by a male relative. "In court I was asked which parent I wanted to live with. I said, 'My mother.' Daddy went berserk. My mother had custody, but I was sent to military academy till I was 18. I remember Daddy leaving me at San Marcos Academy, near Houston. He watched while they showed me how to make a hospital tuck in the bed. He told me to stop crying and be a man. Then he left." The singer is the great-grandson of outlaw John Wesley Hardin; a renegade heritage he's proud of. That said, it's not impossible to imagine his own stubborn machismo (on matters of gender politics and racial integration, Proby is not what you'd call a liberal) being accommodated within the US military. He recalls how, despite being "shy—then and now" , he was seduced instead by rock and roll. He was 17 when his stepsister, Betty, two years his junior, started dating Elvis Presley. "I came back one night," he says, "and there's this Cadillac in the drive, with polka-dot seats. Elvis started going with Betty, and he stayed with us when he was in town. One evening my mother made fried chicken; she put out her linen napkins. When Elvis had finished, he wiped his mouth with the tablecloth. He said: 'Thank you ma'am. Best chicken I ever tasted.'" Proby can still do a perfect impression of Presley, or Eddie Cochran, whose girlfriend Sharon Sheeley befriended the Texan after he ran away to Hollywood, aged 18. Sheeley helped get him a writing contract at Liberty Records. "Back then," Proby says, "I was known as Jett Powers." He'd borrowed Jett from James Dean's name in Giant, and the surname from actor Tyrone Power. Under the patronage of Sheeley, he was hired to record demo versions of new Elvis Presley songs, for the star to study before a film shoot. He wrote a number of hits for Liberty and dated Dottie Harmony, a former girlfriend of Presley's. It was a relationship which ended in a mixture of jealousy and loathing that was to serve as the template for subsequent liaisons, such as his volatile first marriage to Marianne Adams, contracted in Los Angeles in 1962. They were together for two years. He says that Marianne, 15 when he proposed, fell short of his expectations of a spouse in several ways, for instance by having sex with two uniformed LAPD officers at once, then stabbing Proby in the back with a butcher's knife. "I came home one night, drunk as a skink," he recalls. "On the floor was a pair of blue panties with a knife through them, and a note saying: 'If these fit—wear them.'" In the early 1990s, PJ Proby completed an autobiography with the assistance of respected ghost-writer Rosemary Kingsland. The final page of the 300-page manuscript is a list of his lovers. Heavily abbreviated, it still runs to 30 names. Well-written though it was, Proby's autobiography came to nothing. His rapport with his co-author, by contrast, was sufficiently troubled to inspire a documentary shown on Channel 4. "He felt the book was worth £100,000," one Proby observer says. "When he didn't get it, he became convinced people were trying to rip him off. This pattern has recurred." Reading the manuscript of PJ Proby, you can't help being impressed by the singer's medieval capacity for vengeance. In one chapter he fantasises about roasting Marianne's filleted body and serving her as steak, with her bones ground into paté. Some of the powder would be sprinkled into punch: " with plenty of fruit and brandy, that we'd share". Proby's extraordinary ascent from Hollywood drunk to UK teen idol occurred in May 1964. For all his talent as a songwriter (he supplied hits for artists including the Searchers and Jackie DeShannon), Proby had also been working as Paul Newman's driver, and had been living off frozen TV dinners that the Bongo Wolf threw down from his bedroom window. "I told Bongo," Proby recalls, "that if I ever became successful, I would take him around the world, at no charge." It was Sharon Sheeley who invented his current stage name, and recommended him to Jack Good. The English producer, with his sharp wit, bold independence of spirit, and Oxford University accent, was a figure Proby took to immediately. "The first thing he said to me was,"—the singer adopts a faultless upper-class accent—" 'You're hired, dear boy. Be at CBS at 10 tomorrow.' " "I said: 'Ten? In the morning?'" Jack Good flew PJ Proby to London to appear on the Beatles' first UK television special, where he was introduced by Paul McCartney as an established American star. Proby says that he boarded the plane wearing garments pilfered from Hollywood sets. "I took Paul Newman's shirt from Left Handed Gun. I stole Russ Tamblyn's boots from Seven Brides For Seven Brothers." The singer believes every detail of this story, though the details sometimes change. Still, it can't have been easy to have been plucked from obscurity only to have his priapic live performances halted by what he still claims to be a conspiracy orchestrated by the late guardian of British morals, Mary Whitehouse. (The manager of the ABC Luton brought the curtain down on Proby on 1 February 1965; three weeks later, following in-depth scrutiny of his ripped trousers in the Daily Mail, he was barred from every major venue in Britain.) "Were you tearing your clothes deliberately?" "No," Proby says. "And I don't blame the tailor. They'd never experienced anything like me in England. Adam Faith and Cliff Richard? They were momma's boys. I was Britain's Errol Flynn, the rough mother of pop. I was Jimmy Dean all busted up. I was Marlon Brando. They wanted rid of me." When he was in England, still on a roll, living in Chelsea with the Bongo Wolf, another housemate was the maverick producer Kim Fowley. ("PJ Proby's life was a mixture of Caligula and The Picture of Dorian Gray," Fowley told me, "without the picture.") Proby saw a lot of John Lennon, who gave him the song: That Means A Lot. It includes the line: "Love can be suicide." In 1966 Proby returned to Los Angeles, where the process of his self destruction gathered pace, with his energies increasingly devoted to his social life rather than his career. He moved into a lavish home where he founded "The Nymphet Club of Hollywood." He has described this as an after-school club for girls aged 11 to 15. He wanted to instil in them "all my standards, set through military training. The one thing I never did was touch the girls." "Didn't you think that there might be something very slightly wrong about this?" "In the South, we married our cousins at 11. Elvis used to take Priscilla to school. If you didn't marry at 12," adds Proby, who has a fondness for saying the most provocative thing he can think of at the time, " nobody would go on your dance card." Judy Howard, his second wife, was close to his own age. He met her at one of his own soirées in LA. "At my parties," he says, "you checked in your clothes at the door. Men were given loin cloths, a hunting knife and a headband with one feather in it. Girls had a loin cloth. They had to see how many feathers they could get off men during the night. I was dressed in a loin cloth with a huge hunting knife. I carried a rifle. Pigs were roasted. We had grapefruits. We had avocados." Howard's family owned the race horse Seabiscuit. She arrived at Proby's wearing ermine. She was blonde, wearing no underwear, and she was smoking. "Immediately," Proby recalls, "I knew this was class. I didn't run a party for classy people. I ran a party for juvenile delinquents. I told her," the singer continues, in what's one of the least credible lines I've heard in the course of this afternoon, if not my life: 'Go away! This is no place for you!'" Proby later called on the heiress and found her naked, filing a $250,000 cheque made out in her name: a combination of circumstances that seems to have a peculiarly powerful effect on him. Once married, though: "We argued like cat and dog. One night, I had this party with a Hawaiian theme. There were grass skirts," Proby recalls. "There was wine. There were oysters. There were lobsters. "The phone rang. Judy answered. I said: 'It's one of your lovers, right?' She said: 'How did you guess?' I picked up this glass table and smashed it. I ran upstairs, shouting: 'You cheating sonofabitch [sic]. I knew it." She visited him in London, not long before she committed suicide, in the early 1970s. Howard, Proby tells me, left a note on either side of her bed: one for her doctor, another for her mother. "There was no message for me." Judy Howard killed herself in La Hiena, Hawaii. It's an indication of the chaotic nature of the couple of years Proby spent in Hollywood, in the late 1960s, that he seems vague as to exactly when it was that his house exploded. He alleges arson; friends say Proby caused the accident himself. He received the news on licensed premises. "I took the pay phone and called my neighbour, Bobby Darin. I said: 'Robert, will you look out and see if my house is still there, please?' He said: 'No, it sure isn't, Jim. Lots of fire engines, but no house.'" PJ Proby was back in England in 1969, playing the part of Cassio in Good's Catch My Soul. The story of Othello, with its themes of infidelity and violent revenge, was one he had no difficulty relating to. He fell in love with Angharad Rees, who was playing Desdemona. In the afternoons he could be found in a theatre above an east London pub, performing in Spider Rabbit, a play by the Kansas-born writer Michael McClure. Proby had the title role, which called for an emotional range seldom required in his previous excursions, B Movies such as The Ghost Of Hot Rod Hollow. Spider Rabbit is "about a man who's half spider and half rabbit. One side of my face was pink and white with black whiskers. The other was made up like an evil spider. I'd bring out fruit and vegetables resembling hearts and testicles, dripping with tomato ketchup blood, and devour them. Then I'd go around with a chainsaw and threaten the audience while eating a cauliflower soaked in tomato sauce, simulating their brains." He asked Angharad Rees to marry him, but his proposal met with little enthusiasm from his prospective in-laws. When the actress left Catch My Soul early, Proby walked out too. It's generally the case with musicians that the aggregate of suffering in their personal lives is less than that in their repertoire of songs, especially if they're influenced by country music, with its preoccupation with drunkenness, infidelity and violent death. But when PJ Proby starts talking about his later career, I get the definite sense that, in his case, the usual ratio of agony to output has been reversed. He has inspired characters in at least two novels—the eponymous hero of Nik Cohn's 1967 classic, I Am Still The Greatest Says Johnny Angelo and Lucky Learoyd in City of Vultures, the 2004 thriller by Ron Ellis. And yet the events that led up to Proby's near-death experience in 1992 would be difficult to portray convincingly in fiction. They all happened, though, and he has the red-top headlines to prove it. The setting for the final scenes of his tragedy was not Beverly Hills, but the Pennine moors. He married his third ' wife Dulcie, a Mancunian croupier, in 1975. "He wanted Westminster Cathedral," Dulcie said. "We got Bury register office." Proby had shifted his centre of operations to Greater Manchester, close to most working men's clubs. At one point he was living in Bolton, performing alongside exotic balloon dancers in a club owned by a trans-sexual. (" He was the first man ever to have his do cut off on television. He used to look after my laundry. Nice guy.") In the mid-1970s he applied to Durham Education Authority, expressing an interest in teaching, but was not recruited. He lost touch with friends like John Morris and Donald Grollman, the Bongo Wolf. [The closest I got to Grollman was a New Orleans number that has been disconnected.] Proby's reputation for unpredictability gathered pace. He returned to the West End to star in Jack Good's 1978 Elvis: The Musical in 1978, but was fired for not sticking to the script. His third marriage was, he concedes, unharmonious. A few months after leaving Elvis, Proby was prosecuted for shooting Dulcie five times with an air pistol. The singer was acquitted. "Dulcie and her friend got drunk," he recalls. "I took a shower. I heard shots. Dulcie said: 'You shot me.' She called the police and they arrested me bigger than hell." Later that year he was fined £60 for attacking Pamela Baglow—described in court as his secretary—with an axe, "for over-spending on groceries". Proby sees the failure of his relationships as the result of women's inability to live up to his ideals. "Did you never think the problem might have been you?" "No. I was living by the standards that we in the South respected. The lady's place is the house. The man brings home the bacon. Girls won't accept that nowadays." Interviewed in 1965, Proby had said: "I have starved before. I can starve again." It was a prescient remark. He drifted into labouring jobs, and acquired sufficient expertise as a shepherd to be in demand around lambing time on the Pennines. In the early 1980s he was muckspreading on Gerald Hardy's farm, outside Huddersfield. He was heavily featured in popular press on account of the rapport he developed with the farmer's daughter, Alison, 14. She left Proby on her 17th birthday, by which time they were lovers. "Do you have no qualms about what you did?" "No. I still think everybody else is wrong. You should marry your wife," he says, with just a hint of dark irony, "then raise her into a good Christian woman. From a twerpy child." In 1985 he was living in the Yorkshire village of Haworth, home of the Brontës, when he was visited by the founders of Manchester-based Savoy Books, Mike Butterworth and his partner David Britton, who has devoted his life to blasphemous sedition. Britton wrote the notorious novel Lord Horror, most copies of which were seized, on publication in 1990, by the Greater Manchester Police "Jim was lying low, after the affair with Alison," says Butterworth. "We wanted to relaunch his career." PJ Proby's collaboration with Savoy produced a number of intriguing recordings, including his versions of Anarchy In The UK and TS Eliot's The Waste Land. "I had no idea who TS Eliot was," says Proby. "But the more I do The Waste Land, the better I get." "One day the world will realise what a genius he is, and by then it will be too late," Britton said. "Proby is a walking piece of art. His talent needs preserving for future generations." After Britton's mother died, the three gathered at her house at Saddleworth, overlooking the scene of the Moors Murders. There, with Proby larking about on the Zimmer frame that had belonged to the deceased, they worked on his single Hardcore: M97002, which, unless I've missed something, remains the most offensive record ever released. ("Everything y'all think is fun," Proby once said, "I think is boring.") Butterworth says Savoy stopped working with Proby, "because he asked for £2,000 to read one poem. I said: 'Jim: it's only nine lines.' He said, 'Maybe—but you will have my voice forever.'" PJ Proby returned to the West End in 1993, when producer Bill Kenwright hired him for Jack Good's musical Good Rockin' Tonite. ("Kenwright," says Proby, "has been my saviour.") He played himself in the 1995 Roy Orbison tribute show, Only The Lonely, and gave an inspired performance, two years later, in the Who's touring production of Quadrophenia. Discord blighted his collaboration with Marc Almond, on Yesterday Has Gone, the single from Proby's 1997 EMI album, Legend. "Nothing," Almond writes in his 1999 autobiography, "had prepared me for the devil in PJ Proby." At one point, Almond claims, Proby, who felt he was being exploited by EMI, turned on the studio engineer. "PJ shouted: 'Have you ever been in prison? I have. I've got a hand grenade and I'm going to take it to the EMI building and blow them up.' He was deadly serious." "You ever see a picture called Red River?" Proby asked The Independent's John Walsh, around this time. "John Wayne and Montgomery Clift? That was us. Monty was a screaming fag who couldn't bring himself to touch a woman." With better luck and a less volatile star, Legend—an accomplished recording that received limited promotion from EMI—might have brought Proby back into the mainstream. While I was writing this article I had lunch with Proby and record producer David Arden who, in the months before James Brown's death, brokered a substantial deal for Brown to record an album of Cab Calloway songs. It might be interesting, I suggested, to take Proby back to his country roots, with more recent songs: how might that awesome voice sound, applied to Nick Lowe's I'm A Mess, Mary Gauthier's I Drink, or Elvis Costello's Indoor Fireworks? Proby looked momentarily intrigued. "Having an idea for PJ is one thing," a friend of the singer's told me. "Getting it done is another. Ask Jack Good." Good, without whose imaginative instinct PJ Proby would never have existed, was not available for interview for this article. In the early 1990s, he described Proby as "Jekyll and Hyde. He has two personalities, fighting for control of him. The demon wants to destroy Jim and, unfortunately, the demon usually wins. If he'd performed as a regular guy would, he'd be bigger than Elvis, bigger than the Beatles, bigger than the Rolling Stones. He is the most bloody talented rock and roll singer in the world. That's the awfulness of it. It's so sad." "Jack hides from me," the Texan says, "because he believes I want him to write me a musical version of The Merchant of Venice." Remorse has never been PJ Proby's strong suit, and he's not a man you'd choose to defend in a balloon debate. He woke up after one of his debauched Chelsea parties to hear Gary Leeds, drummer for Scott Walker, on the phone, saying: "Mother—please—send me money. PJ Proby is a debauched pervert." That said, Proby's indisputably appalling behaviour has abated since he became sober. Humiliation has failed to drive him back to the Bourbon. "Why do you think your alcoholism developed as rapidly as it did?" "Alcohol took away the pain. It stopped me thinking about things I didn't want to think about." "Such as?" "My first wife... I'd watched momma, and what she did to men." "In terms of what?" "In terms of not being faithful to my father." "You described yourself earlier as shy; not an adjective people associate with you." "I drank because it gave me courage to do things I wouldn't normally do. " "Such as?" "Approach girls." The excesses in PJ Proby's behaviour, according to Marc Almond, have their origins "in fear. His uncertainty, isolation and suppressed addiction have left him worried." Live performance, Proby concedes, makes him nervous. He's just begun one of his rare solo tours; his dressing room is his Winnebago, which he parks outside a venue in ludicrously good time. He recently arrived at a theatre in Birkenhead 36 hours before he went on stage, betraying no anxiety, and captivated his loyal audience. "Soon after I stopped drinking," he recalls, "I went on The Michael Barrymore Show. I was frightened. Before we started, Michael asked me if I had any Valium; I said no. Afterwards, he kept asking what it felt like to perform without drink or tranquillisers. I realised that working without alcohol wasn't only as good, but better. I have no problem confronting anything now." "Even failure?" "Even failure. I don't have one penny to my name." If there's one emotion he exudes, it's the frustration of a player who believes he has one great game left in him. His next concert, at Carnegie Hall, may be in Dunfermline and not Manhattan, but PJ Proby isn't ready to give up just yet. "I keep this garden as a reminder of the paradise I lost," he tells me. "Back in the days when I had everything, the yard was always well-manicured; the lawns cut to a handsome sight. This garden reminds me that, every day, there is work to be done, if I want to climb out of the weeds." We've talked for five hours by the time he starts up the battered Cadillac that he's kept like a badge of honour, and makes the short drive down to Evesham. It's a beautiful late-summer afternoon; when we reach the station car park, passers-by shield their eyes to look at him. Proby, who once relished this sort of attention, doesn't return their stares, but drops me off and heads back into the autumn sunshine, waiting for a thunderstorm to bring him some rest. •

|

| Main Records Page | Artist Index | Singles | Albums | Record Articles | Music Links |