| HOME | BOOKS | COMICS | RECORDS | NEWS | PEOPLE | PICTURES | ORDERS | HISTORY | office@savoy.abel.co.uk |

|

Lords of Horror: The Trials and Triumphs of Savoy Books

b y Q u e n t i n D u n n e

Penny Blood #11 (2008) |

JACK NICHOLSON ONCE COMMENTED regarding the responsibility of an artist, "You've got to keep attacking the audience and its values." If this is true, no one can accuse Manchester, England-based publishing house Savoy Books, of shirking its responsibility. Indeed, Franz Kafka's quote, "I believe that we should only read those books that bite and sting us. If a book does not rouse us with a blow then why read it?" is featured on Savoy's website, and with good reason. No contemporary publishing house has done what Savoy has over the last several decades, creating and distributing some of the most idiosyncratic, iconoclastic, confrontational, and downright Dionysian art and literature imaginable. While the term 'edgy', as applied to the arts, has become a kind of coveted marketing tool which carries an implicit message that if you enjoy a work deemed 'edgy' by critics, you have a certain hip quality, the adjective becomes even more quaint, almost antique, in relation to Savoy's material, the most extreme of which, such as its What if Hitler had won?-inspired Lord Horror series, conjures up a nightmarish netherworld which has long ago transcended the edge.

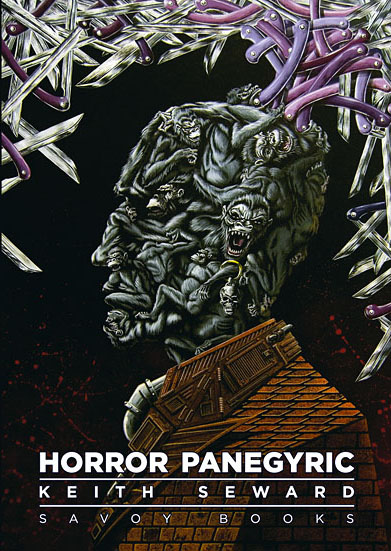

Horror Panegyric (2008). Cover art by John Coulthart.

BEGINNINGS The spiritual genesis of Savoy Books began long before any of its founders were born. From January to December 1896, Leonard Smithers published The Savoy, a magazine with progressive sensibilities and some impressive contributors, including WB Yeats and George Bernard Shaw. In addition to his publishing activities, Smithers was a bookdealer with a professional taste for erotica and a personal taste for the erotic. His friend Oscar Wilde once said of him, "He loves first editions, especially of women: little girls are his passion. He is the most learned erotomaniac in Europe." His fondness of the flesh found other expressions as well. Among the items he sold were books bound in human flesh. Small wonder that nearly a century later, a pair of ambitious young Brits ready to make sure uncompromising literature was available to those who were interested would reprise the magazine's name. And while Smithers and company may have provided inspiration to the duo, their hungry and rebellious natures were all their own. In 1976, Michael Butterworth and David Britton founded Savoy Books in Manchester. Originally, the company's mission was to publish out-of-print or otherwise neglected genre literature and bring it to the attention of the British public. Moved by the idea of giving quality re-releases to the work of such writers as Henry Treece and Jack Trevor Story, they did just that, successfully bringing such offbeat and imaginative works as The Golden Strangers and Screwrape Lettuce to the public at large via international outlets. They also sold erotica, vinyl bootlegs, comic books, and underground zines in their local area outlets, offering both quantity and quality of material for those with more adventurous tastes. But if Savoy was a labor of love by two men who truly believed in the power of art, it was soon apparent their labor was not loved by all. In November of 1980, what would eventually turn out to be only the opening salvo in an epic struggle with the Manchester authorities and its legal system began when the Savoy offices and its retail outlets were raided and thousands of pounds of material seized on the grounds that, under Section Two of the Obscene Publications Act, Savoy was selling, well, obscene publications. Novels such as Samuel R Delany's The Tides of Lust and Charles Platt's The Gas were confiscated and seven softcore paperback novels, including Kenneth Harding's Something for the Boys and Cruel Lips by Marcus Van Heller, were the focus of the prosecution. To add insult and more injury to injury, the boys at Savoy had just signed to be the UK paperback publisher of Cities of the Red Night, the most recent book by one of their heroes, William S Burroughs. The legal costs brought on by the raid and more like it, however, drained Savoy's financial resources and the deal with Burroughs never came to fruition. Britton, meanwhile, was found guilty under Section Two and sentenced to 28 days in prison, of which he served 19. Leading the charge against Savoy was James Anderton, Chief Constable of Greater Manchester Police. Anderton was a vocal, some would say vociferous, Christian whose arch-conservative views on homosexuals and AIDS (he advocated criminalizing homosexuality and declared those with AIDS were, "swirling in a cesspit of their own making") earned him the nickname, "God's Copper." Yet, if Anderton was occasionally mocked, he still wielded great power and for many years he was Javert to Savoy's Jean Valjean. He raided their shops and confiscated their material more than a few times (including once on the very day Britton was released from his prison sentence), and dragged them through the courts, forcing them to spend great amounts of time and money in defense of their right to publish and sell their material. Whatever self-doubt he may have had about hounding the company was likely vanquished by his professed belief that he was an instrument of God's divine will. Curiously, though, it's possible this very push-and-pull between artist and censor, a certain sadomasochistic dance if you will, may have lead Savoy to produce more inspired work than if they had simply been left alone. Does Butterworth agree? "Absolutely. While fighting the court cases, I became conscious of the notion that I was part of a battle that is continuous through time. I just happened to find myself in the driving seat, that's all. It's a battle of the freedom of the individual against the repressive nature of societies. Such struggle is probably necessary, because like all wars, it's a process that forces invention, and things then improve. The irony is that you find yourself in the end thinking that it's productive to allow the repressives the right to free speech as well! Continuing the 'attacking the audience' theme, to create anything, you have to have battling opposites. Ideas are the sparks that fly off!"

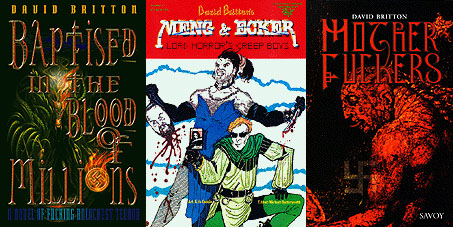

Baptised in the Blood of Millions (2001); Meng & Ecker #1 (1989);

THE BOYS AT SAVOY During the trying experiences of battling Anderton and a court system in a country which had no Constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of speech, Savoy never buckled under the pressure or divided against itself. To this day, Savoy seems to have a teamwork ethic of loyalty, which accounts for how long the principals have not only worked together, but genuinely supported one another through the company's various struggles. One of the subtle but telling signs of the deep bond among the Sayoyans can be found in the way Butterworth frequently uses the term 'we' in response to interview questions. But just who are the men behind what Jim McClellan of i-D magazine dubbed, "The strangest publishing company in the world"? To have his work appear in that publication was of significance personally as well as professionally."New Worlds, had a profound effect on me as a writer. It also led to me wanting to become a publisher." In 1976 he and Britton launched Savoy in which soon, of course, Anderton would take a deeply personal interest, and Butterworth would find himself at the center of many censorship struggles. While Savoy has been dragged through legal and political controversies more than once, Butterworth himself is wary of the political system itself. "None of us are political, and we have been accused for this shortcoming," he admits. "David and I decided ages ago that life is too short. Politics has adherents in droves, and we decided we would devote ourselves to making our art. Looking at our work, some people would say we must be ultra-right wing, but in fact, we're a political mixture, generally left of center. Speaking for myself, I feel I've become more – what some may call 'right wing' – as I've gotten older, but I don't see it as right wing. To me, I see it as common sense. The experiences that older people have accumulated make them see further or deeper than perhaps they use to do. For instance, now I am older I can see how society has to be bound by something, why some laws are so important, to protect the society we've got. But not all laws, not the ones that have passed their useful purpose or for which there is a consensus to change as younger generations spring up and society changes or evolves."

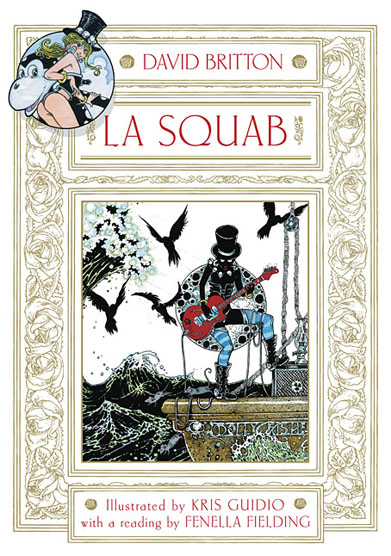

La Squab: The Black Rose of Auschwitz (2012). Cover art by Kris Guidio.

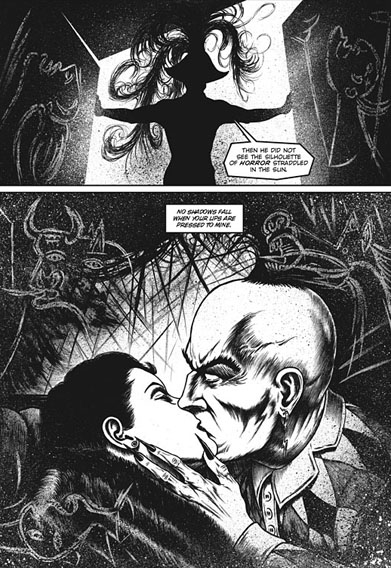

Despite Savoy's often confrontational, occasionally combative, nature and controversial reputation, Butterworth is capable of great generosity of spirit even towards those with whom he holds diametrically opposed viewpoints. He once listed, for example, American feminist Andrea Dworkin, the author of Pornography – Men Possessing Women and advocate of banning pornography, as one of his favorite writers. Was the champion of free speech, erotica, being ironic or was this principled respect for Dworkin having the courage of her conviction? "The latter," he responds. "But we also respected her because she was a great writer, whom we compare with Burroughs. Personally, I also sympathized with her because she suffered badly as a woman, as an underdog in other words, in an unequal society. Her experience inspired her, in both her fiction and non-fiction, and was a lesson to us. She was introduced to us by Michael and Linda Moorcock, who were her friends, and supporters of her campaigns. As a person, Andrea was an incredibly nice, kind woman, nothing like the ogre that she was painted as being by some. We had a lot of respect. It wasn't just Savoy being contrary. And she was a very good analyst of men's porn. She knew exactly what turned men on." Despite his respect for someone like Dworkin, he knows engenders the same goodwill and has a sober assessment about its place in England's literary landscape. "Most people in the UK who support us do so because they believe we have a right to say what we do, but many of them do not approve of us doing it. That's sad, because it makes us feel our work has few real appreciators here. However, we have to be grateful these principled people who have kept us out of jail more than we would have been. "But some of this back-handed tolerance is laziness, a failure to understand us properly, so they don't try to take us seriously. And some of it's peer familiarity. Because they've always known us and have come to accept our 'quirks,' they don't actually examine our work properly. Whenever we manage to take these 'objectors' to one side, invite them into the Savoy office, explain ourselves and they meet us as people, things then improve. They leave with a different regard to the work." Butterworth is aware, though, of a small turning of the tides. "After Keith Seward's perceptive reading and understanding of Motherfuckers, and the subsequent tribute he penned to the Lord Horror cycle in Horror Panegyric, our characters have taken on a new significance. Suddenly, we are being taken seriously by a smarter set. Now, that's scary!" John Coulthart is a self-taught artist and illustrator (who's quick to point out that 'self-taught' shouldn't carry quite the mystique it does, and credits his mother's art school training as a benefit to his own development) who started as a fan of Savoy's output, and ended up becoming one of the key members of the team itself, eventually collaborating on, among other works, the Lord Horror Reverbstorm comic series with Britton. He has found the collaborative nature at Savoy highly rewarding. "The collaboration mainly involved discussing things as we went along. Dave and Mike set the ball rolling with a cast of characters and an initial scenario, then we went on from there. Every now and then, I'd ask for some lines of dialogue and once a page was drawn we'd have our weekly meeting to talk about it. The series grew organically as a piece of improvisation, something which is anathema to the mainstream comics world, which prefers to have every last detail scripted beforehand. I don't believe the series would have attained the wildness and weirdness it does if we'd tried to plan everything out at the beginning." And why the decision to illustrate Reverbstorm in black-and-white? "Color isn't always an advantage, and can be a distraction if not artfully applied. I admire Burne Hogarth's artwork a great deal, but prefer to see his work in black-and-white – as in his Jungle Tales of Tarzan collection – than in color. Black-and-white gives more emphasis to line-work, detail, and masses of light and shade. It's also far more suited to the creation of a mood. My own comics drawing has given a lot of emphasis to shading, something which is made redundant when the pages are colored. Shading gives a drawing texture which color often has difficulty matching."

Reverbstorm. Art by John Coulthart.

Coulthart clearly relishes the freedom his work with Savoy has allowed him. "Dave's written works had already established a precedent for me. There's historical material in there, and characters based on real people, but the whole is presented as a phantasmagoria. I can't imagine anything being cut for reasons of being too much since 'too much' was part of the point. As The Cramps would say, 'How far can too far go?' Reverbstorm spins off from intellectual concepts such as James Joyce's line in Ulysses about, 'the nightmare of history' that twists into something which contains the history but which is presented as a nightmare. Joyce did this himself in the 'Nighttown' chapter of Ulysses, which depicts a journey through Dublin's brothels as a Boschian nightmare full of bizarre transformations, even going so far as to include the end of the world. Joyce was well aware that strict realism wasn't always the best way to deal with reality." Coulthart's artistic influences are not limited to the work of other artists he admires, but encompass music – he has created album covers for several bands – and architecture, the latter of which holds particular interest for him. So much so that sometimes simply looking through a book of pictures of buildings old and new can provide a muse. Of his political leanings, Coulthart says, ''I've always described myself as an anarchist. I'm not interested in the party politics of left or right." Britton does not given many interviews, but the people who are most familiar with him and his work have some words to offer. Says Butterworth of his long-time friend and collaborator, "David claims he owes sixty percent of his emotional drive in his writing to first generation 1950's American rock 'n' roll. He told me, for this interview: 'The obvious practitioners, Jerry Lee Lewis and Little Richard, together with the more obscure Larry Williams and Charlie Feathers, in particular, supply the pounding prose of Motherfuckers. Then, later on, the whole 1960's scene. I consider the heart of what I do comes from Captain Beefheart and Frank Zappa and Michael Moorcock's 'New Wave' of science fiction magazine, New Worlds. This 'feel' of rock n' roll has to be in the writers Michael Butterworth and I publish. Lord Horror himself came from us working with PJ Proby, who had a first-hand stink of genuine rock n' roll rebellion. I see Proby as the missing link between Gene Vincent and Johnny Rotten.' He doesn't think it's probably wise to go much past the 60's musically because very little has touched him in the way that those early rock n' rollers did, but he says: 'When pushed, Niggaz With Attitude, particularly the album Straight Outta Compton, or something by The White Stripes, would be an aroma that I would like a reader to experience when they open one of my books.'" Offers writer Keith Seward, ''As a writer, David Britton has more balls than anyone else alive – and he has proven this by going to jail not once but twice on behalf of the written word."

LORD HORROR The character who would become most popularly (a word simultaneously proper and ironic here) associated with Savoy's literary output was Lord Horror. Curiously, for a figure who rampages across the pages of Britton's novels and adult comics, Lord Horror was first introduced to the public in 1986 as, of all things, a vocalist on a 12" single distributed by Savoy. Of course, Savoy being Savoy, the song was a savage and slashing cover of New Order's 'Blue Monday'; one seemingly designed to perplex listeners as much as to please them. And, oh yes, the single was credited to the Savoy Hitler Youth Band. The following year, an image would be added to the voice. Another 12" single was released, this time a cover of Iggy Pop's 'Raw Power'; with the back of the sleeve serving to introduce Lord Horror, via Kris Guidio's rendering. With Britton and Butterworth as the guiding creative force, Lord Horror would erupt two years later with the publication of a novel Lord Horror, a work of singular force and vision whose eponymous title would be the first and last traditional thing about it. Although the mixture of imagination, daring, and pitch black satire intrinsic to the Lord Horror character might make it seem as if it sprang full-blown from the fever dream of an especially, ahem, colorful dreamer, the character does, in fact, have its roots in a historical figure. William Joyce (who would eventually come to be known as Lord Haw Haw) was a New York-born and Ireland-reared Catholic who eventually settled in England and joined the British Union of Fascists, where he served as director of propaganda and, later, deputy leader. Joyce moved to Germany in 1939 and became a naturalized citizen one year later. He soon became the most (in)famous Nazi propaganda broadcaster on the Germany Calling radio program due to his vivid and vitriolic advocacy of fascism, which included taunting England to surrender before facing inevitable and humiliating defeat. Defeat, though, would eventually come to Joyce himself, when he was captured by British forces then tried and convicted of high treason. Upon his death by hanging, at age 39, he remained unrepentant, even defiant, stating he was proud to die for his ideals. His execution was the subject of controversy, as he was, after all, an American citizen convicted of treason under the British flag.

Reverbstorm. Art by John Coulthart.

In the hands of many writers seeking to portray Joyce, he might have emerged as a tragically flawed man whose better self was warped through the sinister but seductive allure of Nazism. But Britton was not like many writers, and he found in Joyce a vehicle with which to dig into the darkest, dirtiest, and deadliest corners of the human psyche, one which has led to Nazism in particular and centuries of genocide in general, and to do so with a go-for-broke vision. If, as Blake said, the path of excess leads to the palace of wisdom, Britton seemed ready to reach for wisdom with both hands, wring its neck, and then find what lay beyond wisdom's broken corpse. During his broadcasts Joyce had been pejoratively dubbed Lord Haw-Haw by a British radio critic. Signaling their intentions from the get-go, Britton changed the nickname to Lord Horror. He and Butterworth set to work, and over four long and arduous years of composition a creation destined to both acclaim (by some) and condemnation (by many) was born. Upon publication of Lord Horror in May of 1989, Savoy's old nemesis Constable Anderton was back and ready for battle. Some prominent figures rallied to Savoy's defense. Acclaimed horror fiction writer Ramsey Campbell proclaimed, "Lord Horror makes most horror fiction look tame and safe. Awesomely grotesque, unstoppably imaginative, hideously funny, it's a truly dangerous work." Meanwhile Douglas E Winter chimed in, "I found neither nasty nonsense nor pornography, but the blackest, if not bleakest, of comedies, written firmly in the Swiftian tradition… Lord Horror indulged in what so called 'right-thinking' people consider the most grievous of sins: to turn all notions of moral fiction on their head… and then laugh." Unfortunately, plenty of those 'right-thinking' people set about making Savoy atone for what they considered its grievous sins. Michael Winner, director of the Charles Bronson Death Wish films (which, incidentally, received their fair share of accusations of fascism), had this to say: "I find the Lord Horror book grossly racist. I would not wish to defend it. This is precisely the kind of book we should be banning." The judge presiding over the case – no jury of peers was allowed to render a verdict – agreed, and Lord Horror became the first novel banned in Britain since Hubert Selby Jr.'s Last Exit to Brooklyn, and Britton himself landed, once again, in jail. Britton, however, would not be deterred and Lord Horror's journey would stretch out over the course of two more novels: Motherfuckers: The Auschwitz of Oz in 1996 and 2000's Baptised in the Blood of Millions. His most recent incarnation would be in the series of graphic (and I do mean graphic) novels entitled Reverbstorm, with art by Coulthart and Kris Guidio. "Dave and I both have a confrontational streak," Butterworth freely admits, "and have each spent a long life channeling this tendency to make our work as excellent as we can, so that for instance, when Lord Horror was conceived, the initial thought of how he should be was discarded, so was the next thought, and the one after that until we arrived at the concept of Lord Horror. He had been Hitler, he had been something else before that, but before pen was set to paper he became William Joyce (aka: Lord Haw Haw). What I am trying to say is that this confrontational tendency we have is the impulse behind a constantly refined alternative universe of characters. David could have used much lesser characters, but he waited for the right ones. In this process, multiplied a hundredfold, and applied in a hundred ways, you can see how a 'philosophy' for Savoy has come about. It isn't just the impulse-to-offend. Any Tom, Dick, or Harry can do that. Jack Nicholson is right when he says the artist has to keep attacking the audience and its values, and we are conscious about the need to shake things up, and we do. But it also comes naturally, from an organic place." In a lengthy and penetrating essay entitled 'Horror Panegyric', Seward passionately defended and celebrated the literary merit of Savoy's most iconic – and iconoclastic – character, Lord Horror himself. (Or perhaps, Lord Horror itself because, as Seward argues, Joyce the man is simply a jumping off point for a surreal, anarchistic journey through an existential hall of mirrors which reflects the absurd brutality of a world in which bigotry, racism, and violence have long flowered in various shapes and sizes.) The first book Seward encountered in the series was Motherfuckers, in which the central characters, Meng and Ecker, are twins who have survived the gruesome 'medical' experiments of Dr Josef Mengele. They now wander in a post-war world, the vicious cruelty they endured having been absorbed and now practiced by them. It's worth quoting Seward at length about the book: "Sure, there are writers who 'push the envelope.' But Motherfuckers does not just push the envelope. It beats at it with fists, kicks, bites, and stabs the envelope. No matter how jaded a reader you are, no matter how much you've read your Henry Miller and Marquis de Sade, this is the book that will leave you feeling bad for the envelope. After Motherfuckers, it will never be the same again."

Reverbstorm. Art by John Coulthart.

CONTROVERSY "Savoy is an incredible story made up of many moving parts," Seward comments. "The police harassment that David Briton and Michael Butterworth have suffered, the championship of not just obscene but of obscure books, the excursions into music that have resulted in the resurrection of PJ Proby, and, of course, the invention of a veritable franchise of Lord Horror productions. All of this achieved in spite of legal hassles, financial dilemmas, and God knows what personal sacrifices." No one can deny Savoy's work, its Lord Horror material in particular, stirs up strong emotions. Then again, a fair amount of work concerning the Holocaust does. It's worth noting, in this context, that some sociologists and historians have argued that, "How did the Holocaust happen?" is not so much the question to be asking as is, "Why don't things like the Holocaust happen more often?" It's a question Butterworth himself has wrestled with. "At the beginning of the 1980's, I set out to try to discover just that, how the Holocaust happened, and I think I managed to arrive at a few unexpectedly commonplace truths, but as to your question, why don't these terrible things happen more often, that is one of the things we were concerned with in Reverbstorm, where we postulate the existence of an eternal ubiquitous city built on the ethnic dead. It is the atrocity of racial cleansing taken to lofty, absurd extremes. As a species, homosapiens is on the brink, unable to adapt to its own advances in technology. I don't believe any longer human extinction will happen. I've become a lot more optimistic and hopeful as I've grown older. The 'gravity' of our civilization is now such that it probably can't be pulled down, no matter how hard some may try. But such views may still come to pass, and Reverbstorm is a valid reflection of them. I see it as a kind of dark speculative fantasy, part prophetic warning as we continue to overpopulate the planet, resorting to barbaric solutions; part bizarre threnody to the primitive tendencies inside us that refuse to go away." Despite Butterworth's eloquent and articulate explanations, Savoy has hardly been welcomed into the publishing mainstream. Yet, during its darkest hours, several people sprang to its defense, for which Butterworth remains deeply appreciative. "Geoffrey Robertson [a noted human rights lawyer and academic], the way he came to our defense has had a profound impact. Without him standing up for us, our work would have been destroyed by the police as soon as it came off the press. As it was, we had a battle to save what we could of our comics. In his defense of us, Keith Seward has moved us greatly. There are others, academic such as Julian Petley and Benjamin Noys, who have taken our work seriously, and have gone into print saying so. Ramsey Campbell gave us a supportive quote at a crucial moment, and Douglas E Winter has been a constant and fearless champion, for which we are very grateful." Still, with the charges of anti-Semitism and fascist sympathies that have been leveled at Savoy in general and Britton in particular over the years (though they have decreased of late), what does a reader like Seward make of such accusations? Indeed, a few of Savoy's most vitriolic critics have suggested comparisons between the Lord Horror books and white supremacist William Luther Pierce's (writing as Andrew Macdonald) book The Turner Diaries, which is widely believed to have been one of Timothy McVeigh's inspirations for the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, which killed 168 people. "I have read The Turner Diaries, and I believe it possesses no literary qualities whatsoever," Seward comments. "It is '…a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.' You could argue its quantifiable impact must indicate some merit, but I would reply that it has the merit of propaganda, not literature. In that sense, The Turner Diaries has more in common with political statements, religious tracts, and toothpaste advertisements than with Savoy Books." Furthermore, while Pierce's novel has been acknowledged by the attackers themselves in several race-related crimes, no one has ever cited any of the Lord Horror books in a similar fashion. But why treat what is arguably the seminal event of the twentieth century in a way that runs the risk of charges of exploitation and gratuity? Why dance on the edge of what many will perceive as excessive gore better suited to one of Lucio Fulci's spaghetti zombie flicks? "The horror genre has always been central to us. Clark Ashton Smith, HP Lovecraft, JG Ballard, even William Burroughs, are in the lineage in which we feel we belong," answers Butterworth. "I think it's fair to say that the last landmark horror books that pushed the genre forward were Clive Barker's Books of Blood. Clive has been very kind to us, allowing us on his television program, Clive Barker's A-Z of Horror, but we differ with him in the sense that he has spoken publicly that he would not do a book that featured the Holocaust. We see the Holocaust differently, as the ultimate horror, to be approached seriously. But I will leave David to finish off this answer. He says: 'To judge [the Holocaust] as a dark fairy tale is not to belittle the terrible happenings that went on there, and we wanted to face them head on, like no other book has. Not to be frightened, but to be hard and intense – and let the readers feel the horror of those dreadful places. We wanted to create characters that come from that ultimate horror. It took a great deal of courage on our part to go against more or less a hundred percent ban on any book that treated the Holocaust from the point of view of Horror. So we are saying, if we will be allowed a degree of hubris, that the Lord Horror books are the twenty-first century yardstick by which horror fiction should be judged. As they say, nobody does it better, nobody does it, period.'"

Reverbstorm. Art by John Coulthart.

ART, ANGUISH, AND ECSTASY Leaving aside the legal issues of freedom of expression and censorship, the best – or, some would no doubt say, the worst – of Savoy's material digs down into questions more primal than the legal definitions of obscenity. It forces the awkward but inevitable issues of what the nature and function of art is. Can, for example, shock value in and of itself be an aesthetic value? Butterworth, for one, does not see any great merit in shock value without some accompanying theme or insight, in his work or in others. "We set out to shock, and David, in particular, deliberately cranks up the ante in our novels and comics and sets everything going in a mad hyper-reality. But there would be no art in what we were doing if it was gratuitous for the sake of it, if we shocked without purpose , just to offend, as some do. 'Value' implies commerce, and although certain 'critics', included among them some judges and policeman and most of the UK media, have confused us with schlockmeisters, we don't see ourselves that way at all." Still, given that anti-Semitism remains a disturbing and persistent reality, both in the hearts of private citizens and on the world stage, it's hardly unfair to ask the question, "Why not put a disclaimer disavowing anti-Semitism at either the beginning or end of Reverbstorm or Lord Horror?" After all, if your intentions are not to stir up racial animosity, why forgo the opportunity to be perfectly clear about that? Surely, a strong and straightforward repudiation of anti-Semitism or bigotry of any kind might have made life just a bit easier for the team at Savoy, not to mention those loyal enough to continue selling and reading the work. Hell, Lord Horror's author bio could mention the simple fact that Britton's father is Jewish. What gives? Not having heard Britton or Butterworth speak on this issue personally, I would hesitate to ask even if I could. Any speculation would be much more fun, but ultimately, of course, just speculation nonetheless. Still, when considering the questions above, two quotes spring to mind, ones that might light the way, at least for this reader. The first is from the late New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael, who wrote in her review of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, "Is there anything more repellent than a clean-minded pornographer?" The other is by Mel Brooks, who once said, "My movies rise below vulgarity." The creator of a character such as Lord Horror, in this context, saves himself from Kael's snarky charge and shows a certain kinship of sensibility to Brooks in not throwing out the easy disclaimer or qualifier. What could be more creepy – or more cowardly – than a writer rubbing the hearts and minds of his readers through page after page after page of some of the most shocking and transgressive material they've read, only to cover himself with a conventional and self-serving paragraph or two letting the world know he's really a swell and decent chap who abhors whatever thoughts might have been stirring you as you toughed your way through his book? No, the author here has, in that respect, the courage of his convictions. Or the confidence of his artistry, for that matter. The work is there to stand on its own. Take it or leave it, and draw from it what you will. A pretty rock n' roll attitude: stubborn and rebellious, but also honorable and true in its refusal to compromise for the sake of expedient comfort. Then again, it might be a paradoxical sign of respect for the reader's intelligence, a willingness, either courageous or fatalistic or both, to let them make up their own minds. Of course, there are certainly clues along the way. For example, one of the quotes found in the pages of Reverbstorm, Volume 1, Number 11, features novelist, literary critic, and, not incidentally, Holocaust researcher George Steiner's quote, "The dark places are at the center, pass them by and there can be no serious discussion of the human potential." And whatever else it does, Reverbstorm takes an unflinching look at the dark places at the center of the human psyche, and it does so with a sort of wild integrity. Offending people isn't hard, but offending people in a truly memorable and unique way is. The seemingly oxymoronic axiom of offending people well is an art not easily mastered, and one sign of it being mastered is that the offending work is alive, the work of genuine talent, not merely someone itching for a literary foodfight. The often-used characterization of Savoy's material as 'politically incorrect' seems, to this humble reader, to be as misguided as it is convenient. Classically defined, political correctness is the elevation of sensitivity over truth. But a work like Lord Horror is neither politically incorrect nor simply incorrect. Or politically correct, for that matter. It simply is. It comes at you with the force of its own nature and plays by its own rules. It is an experience. As Butterworth himself has noted, the work offers not a message, but a vision. This is what makes it unpalatable to many and exhilarating to others. Some may feel it's both at once. The tension between the emotionally disturbing subject matter and the obvious talent that went into writing it gives the material both its pop and its pulse. It's a skillful mixture that can cause the reader agony or ecstasy, but it won't cause indifference. "We've said on a number of occasions that what people meant by 'adult comics' when these things were first being mooted in the 1980's, were invariably misconstrued to be nothing more than adding explicit sex and violence to the usual superhero scenarios," explains Coulthart. "Our conception of adult comics was comics for adults, not comics with 'adult' content. In other words, only someone who's reasonably well-read and who recognizes some of the cultural references – and then sees how those references interrelate – will get anything substantial from the Reverbstorm series. Kids might like some of the artwork, but the content will be varying degrees of confusing or meaninglessness. This was confirmed the few times we went to conventions and found our stall completely ignored by teenage comic readers. "Regarding censorship," he continues, "you have to do the work first. Be true to that and worry about the reaction later. Otherwise, you'd be looking over your shoulder the whole time. Dave Britton's mythos concern fascism and the Holocaust; no one should try and soft-pedal either of those subjects." Again, Seward weighs in: "By its nature, transgression is a very obvious quality. It screams in your ear. Literariness, however, tends to be subtler. It may only whisper. For that reason, everyone hears the transgressions, but only a few, those with more sensitive instruments, pick up the literary merits of a work. Eventually those few will make a compelling case for the literary merits, and meanwhile the headbangers – the ones who read a book for the loudness of the volume – will take the merit on faith or perhaps not even care. "That being said, if people enjoy a book because it tests their mettle, that's fine. Every work of genius tests your mettle in some way – perhaps by offering a challenging form, a difficult moral, or a vision of life that upsets your own." Is there a possibility, though, that some covet the material, not because of what they get from it, but because it gives them a certain cache, a certain sense of being in the know? And if so, what would be the implications of such an attitude? "To enjoy a book because it's a kind of secret among cognoscenti is to enjoy it for the wrong reasons – to treat it as a fashion item, a badge of your hipness," Seward argues. "A book ought to sink or swim on its own literary merits, and that's what you should read it for. Generations of people have read Paradise Lost, for example, and that doesn't diminish my joy when Milton has Satan say, 'Awake, arise, or be forever fallen.' If millions of people were to read Motherfuckers, that wouldn't detract one bit from the pleasure that the book has to offer."

Reverbstorm. Art by John Coulthart.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES AND OTHER DIRECTIONS Since its inception, Savoy has managed to have its hands in everything from the republication of neglected novels to the publication and distribution of new ones. It has sold science fiction, fantasy, erotica, graphic novels, and musicology books on AC/DC and KISS, bootlegs as well as original records of artists. It has resurrected the career of faded rocker P J Proby, who would not only record songs for Savoy, but read the audio version of Lord Horror. And so forth. It is unique among England's cultural landscape in its eclectic offerings. Along the way, though, some of its proposed projects have had to be scrapped, such as the aforementioned UK paperback publication of William Burroughs's Cities of the Red Night. Other projects that did not reach fruition as a result of the time and money lost by Chief Constable Anderton's repeated raids include a novel of science fiction erotica by Philip José Farmer. Were there other casualties of Savoy's legal hassles? "There were," answers Butterworth. "A Gerald Scarfe book [the acclaimed cartoonist who provided the artwork for both the album and film Pink Floyd The Wall] book we planned to do, also Heathcote Williams's Severe Joy, a collection of 60's and 70's work, and the Brion Gysin book of interviews Here to Go: Planet R101 that I commissioned and put so much work into and had to let go…" Despite these missed (or, perhaps more accurate, stolen) opportunities, Savoy still sees itself expanding into new ventures. Says Butterworth, "Theatre and film are two of the things missing from our media umbrella. We would still like to get Lord Horror and Meng and Ecker performed or filmed."* Were Lord Horror ever to reach the big screen, what actors does he feel could possibly embody such a character? "There have been several people we thought could have played Lord Horror, for instance, the young Rutger Hauer. David thinks Daniel Craig, who plays James Bond, and who played Francis Bacon's boyfriend in Love is the Devil could play him today. Julian Bleach, who played Flay in David Glass's stage adaptation of Mervyn Peake's Gormenghast, would make a convincing Lord Horror." Meanwhile, Coulthart continues to shape Reverbstorm into a form of its highest possible quality. ''I'm putting together the whole series as a single volume book which will be the definitive edition. The artwork has been scanned and re-lettered. Some minor textual amendments have been made, and I've added some additional pages. We're also adding 32 pages of art from Hard Core Horror #5 as an opening prelude and the book will include the eighth and final part of Reverbstorm, which was left half-completed. I'll be finishing that at last." **

LEGACY While Savoy has had its share of struggles through the decades, it appears that it has not just triumphed over the James Andertons of the world, but is also beginning to flourish at large in the Internet age. What effect has the World Wide Web had on Manchester's most infamous publishing house? "In terms of the mechanics of production, it's been immense," says Butterworth. "Email communication, and the instant access to information, means we can get books out with less effort than we used to, and do more ambitious books. And it's amazing how easily you can find people and also how easily they can find you. As the Internet grows, it will turn publishing into a cottage industry." As a result of such technological advances, not only can readers easily locate such books as Colin Wilson's The Killer and Jack Trevor Story's Something for Nothing on the Savoy website, but the very titles that Anderton's forces tried so hard to keep away from the citizens of Manchester, England, are now readily available to the citizens of Manchester, New Hampshire. And this may be one of the most important aspects of Savoy's legacy, as it makes them a link in the long chain that champions the artist over the censor and the individual over the state, the "battle that is continuous through time," as Butterworth described it. Though often difficult, a glance at recent history makes clear they've been on the right side of that battle. After all, the records of Elvis and the Beatles continue to sell long, long after those who burned and banned their records have faded into obscurity. Once outlawed works such as Story of O and the writings of the Marquis de Sade are now sold at Borders and Barnes and Noble. The once scandalous Hugh Hefner now has his own reality show, The Girls Next Door, which presents him as a positively benign figure. Yes, Savoy has been a link in this chain, a fighter in the battle that is continuous through time, but that should never obscure the fact they've also been a publisher of genuinely interesting and insightful material. Still, it's fair to ask, with Savoy's legal battles having abated greatly, does Butterworth ever look back, and feel a perverse nostalgia for the days when he was regularly tussling with the powers that be? "Only in the sense that we miss the energy of those days," he says. "Nostalgia for things past…" Savoy could have long ago saved itself a lot of troubles by moving closer to the mainstream, by being more cautious of and deferential to Manchester's legal and cultural authorities. This, alas, was not meant to be. But could anyone really have blamed them if they'd decided to take the path of, if not least resistance, less resistance? After all, for a company that has prided it self on its rock n' roll attitude, don't they know that one-time anti-establishments rebels such as The Who and The Rolling Stones have been touring under corporate sponsorship for years? Why, even Bob Dylan has licensed his songs for use in commercials. Hasn't so much of the counterculture already been, through either accident or design, absorbed by the dominant culture? In asking these questions, I can't help but think of a passage in Flannery O'Connor's Wise Blood, in which an incredulous woman discovers the protagonist wrapping barbed chicken-wire around himself in order to imitate the wounds of Christ, and scolds him: "Well, it's not normal. It's like one of them gory stories, it's something that people have quit doing – like boiling in oil or walling up cats," she said. "There's no reason for it. People have quit doing it." "They ain't quit doing it as long as I'm doing it," he said. That, as much as anything, seems to convey the spirit of Savoy. As long as it's around, people ain't quit doing what they're doing. In the spirit of literature itself, in which the reader is the ultimate judge, perhaps it's only fitting to give the final word not to the men at Savoy, but to one of their readers, one of the people who has been most excited and engaged, even moved by its work. "I can't think of anything like Savoy in America, or elsewhere," says Seward. "They're not strictly a publisher, writer, musician, or impresario, though their work includes all those functions. They're not a movement – they don't write manifestoes, like the Dadaists, and they don't have a headquarters, like the Bureau of Surrealist Research, from which André Breton was constantly banishing people. Savoy consists of two independents – and a few irregulars sucked into their wake – who pursue their work with the stubborn, crazy passion of obsessives. They're less a movement than a folie a deux – and if such a thing exists in America, it is probably locked away in an institution somewhere." * Since this interview was conducted Gareth Jackson has completed his film, Lord Horror: The Dark and Silver Age, which is available as a free download. A trailer can be viewed here. ** Reverbstorm the book is now available here. John Coulthart's official website. Keith Seward's official website. Horror Panegyric is now out of print but can be read for free here. Lord Horror, as read by PJ Proby, is available through iTunes. Note: Savoy has put the Appendix to the Reverbstorm series on its website here. "That," Coulthart notes, "explains the references for those that want them." An updated Appendix is also available in the Reverbstorm book. |

| Main Comics Page | Lord Horror | Meng & Ecker | Other Comics | Articles | The Reverbstorm Appendix | Links |